Researchers digging at the Cerutti Mastodon site, an archaeological site from the early late Pleistocene epoch near San Diego, California, found animal remains and stone tools that show the first humans were living in North America much earlier than previously thought.

A concentration of fossil bone and rock at the Cerutti Mastodon site: the unusual positions of the femur heads, one up and one down, broken in the same manner next to each other are unusual; mastodon molars are located in the lower right hand corner next to a large rock comprised of andesite which is in contact with a broken vertebra; upper left is a rib angled upwards resting on a granitic pegmatite rock fragment. Image credit: San Diego Natural History Museum.

The Cerutti Mastodon site was discovered by San Diego Natural History Museum researchers in November 1992 during routine paleontological mitigation work.

This site preserves 131,000-year-old hammerstones, stone anvils, and fragmentary remains — bones, tusks and molars — of a mastodon (Mammut americanum) that show evidence of modification by early humans.

An analysis of these finds ‘substantially revises the timing of arrival of Homo into the Americas,’ according to a paper published this week in the journal Nature.

“This discovery is rewriting our understanding of when humans reached the New World,” said Dr. Judy Gradwohl, president and chief executive officer of the San Diego Natural History Museum.

Until recently, the oldest records of human activity in North America generally accepted by archaeologists were about 15,000 years old.

But the fossils from the Cerutti Mastodon site — named in recognition of San Diego Natural History Museum paleontologist Richard Cerutti, who discovered the site and led the excavation — were found embedded in fine-grained sediments that had been deposited much earlier, during a period long before humans were thought to have arrived on the continent.

“When we first discovered the site, there was strong physical evidence that placed humans alongside extinct Ice Age megafauna,” said lead co-author Dr. Tom Deméré, curator of paleontology at the San Diego Natural History Museum.

“Since the original discovery, dating technology has advanced to enable us to confirm with further certainty that early humans were here much earlier than commonly accepted.”

Since its initial discovery, the Cerutti Mastodon site has been the subject of research by top scientists to date the fossils accurately and evaluate microscopic damage on bones and rocks that authors now consider indicative of human activity.

In 2014, U.S. Geological Survey geologist Dr. James Paces used state-of-the-art radiometric dating methods to determine that the mastodon bones were 130,700 years old, with a conservative error of plus or minus 9,400 years.

“The distributions of natural uranium and its decay products both within and among these bone specimens show remarkably reliable behavior, allowing us to derive an age that is well within the wheelhouse of the dating system,” Dr. Paces said.

The finding poses a lot more questions than answers.

“Who were the hominins at work at this site? We don’t know. No hominin fossil remains were found. Our own species, Homo sapiens, has been around for about 200,000 years and arrived in China sometime before 100,000 years ago,” the researchers said.

“Modern humans shared the planet with other hominin species that are now extinct (such as Neanderthals) until about 40,000 years ago. If a human-like species was living in North America 130,000 years ago, it could be that modern humans didn’t get here first.”

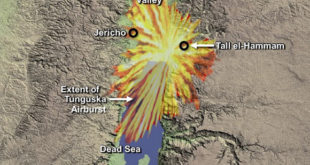

“How did these early hominins get here? We don’t know. Hominins could have crossed the Bering Land Bridge linking modern-day Siberia with Alaska prior to 130,000 years ago before it was submerged by rising sea levels,” they said.

“For some time prior to 130,000 years ago, the Earth was in a glacial period during which water was locked up on land in great ice sheets. As a consequence, sea levels dropped dramatically, exposing land that lies underwater today.”

“If hominins had not already crossed the land bridge prior to 130,000 years, they may have used some form of watercraft to cross the newly formed Bering Strait as glacial ice receded and sea levels rose.”

“We now know that hominins had invented some type of watercraft before 100,000 years ago in Southeast Asia and the Mediterranean Sea area. Hominins using watercraft could have followed the coast of Asia north and crossed the short distance to Alaska and then followed the west coast of North America south to present-day California.”

“Although we are not certain if the earliest hominins arrived in North America on foot or by watercraft, recognition of the antiquity of the Cerutti Mastodon site will stimulate research in much older deposits that may someday reveal clues to help solve this mystery.”

Stone tools from the Cerutti Mastodon site: (a-d) anvil; (a) upper surface; boxes indicate images magnified in b-d; dashed rectangle, magnified in b, small dashed square, magnified in c and solid square, magnified in d; (b) cortex removal and impact marks (arrows); (c) striations (arrows) on the highest upper cortical surface ridge; (d) striations (diagonal arrows) and impact marks with step terminations characteristic of hammer blows (vertical arrows). (e–i) hammerstone; (e) impact marks; the box indicates the magnified images in g and h; (f) upper smoothed surface; (g) deep cracks and impact scars (arrows); (h) impact scars from g, showing results of three discrete hammerstone blows on an anvil (arrows); the large flake scar (central arrow) has a clear point of impact with radiating fissures; the small scar (right arrow) has a negative impact cone and associated scars and fissures preserved beneath a layer of caliche; (i) striations (arrows) and abrasive polish on upper cortical surface (near black North arrow in f). Scale bars – 5?cm (a), 2?cm (b, g, h), 1?mm (c, i), 2?mm (d), 10?cm (e, f). Image credit: Holen et al, doi: 10.1038/nature22065.

The authors also conducted experiments with the bones of large modern mammals, including elephants, to determine what it takes to break the bones with large hammerstones and to analyze the distinctive breakage patterns that result.

“It’s this sort of work that has established how fractures like this can be made,” said co-author Daniel Fisher, a professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Michigan, and director of the University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology.

“And based on decades of experience seeing sites with evidence of human activity, and also a great deal of work on modern material trying to replicate the patterns of fractures that we see, I really know of no other way that the material of the Cerutti Mastodon site could have been produced than through human activity.”

“There’s no doubt in my mind this is an archaeological site,” added lead co-author Dr. Steve Holen, director of research at the Center for American Paleolithic Research.

“The bones and several teeth show clear signs of having been deliberately broken by humans with manual dexterity and experiential knowledge. This breakage pattern has also been observed at mammoth fossil sites in Kansas and Nebraska, where alternative explanations such as geological forces or gnawing by carnivores have been ruled out.”

The scientists also created 3D digital models of bone and stone specimens from the Cerutti Mastodon site.

“The models were immensely helpful in interpreting and illustrating these objects,” said co-author Dr. Adam Rountrey, collection manager at the University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology.

“We were able to put together virtual refits that allow exploration of how the multiple fragments from one hammerstone fit back together.”

“The 3D models helped us understand what we were looking at and to communicate the information much more effectively.”

_____

Steven R. Holen et al. 2017. A 130,000-year-old archaeological site in southern California, USA. Nature 544: 479-483; doi: 10.1038/nature22065

#Bizwhiznetwork.com Innovation ΛI |Technology News

#Bizwhiznetwork.com Innovation ΛI |Technology News